#digiRoundtable 2025, Foto: Dušan Ristić

Museums' discourses in the digital age: Pluralizing and engaging with heritage

Von:

Dušan Ristić (Universität Graz), Graz

Digital technologies not only facilitate the documentation and preservation of heritage but also create opportunities for new dimensions of heritage to emerge. Heritage is not merely something material, a piece of content, or an object to be digitised. Its use, whether by professionals involved in its digitisation or the public that ‘consumes’ it, inevitably raises questions about the production of meaning. The research project DISCULTHER: Digitalisation of Cultural Heritage as Discursive Practice: Mapping the Museums and Citizens-led Initiatives in Graz and Novi Sad addresses this issue, starting from the premise that the meanings of heritage can be explored through the study of digitalisation. In other words, digitalisation is approached in this research as a discursive practice. Moreover, the research differentiates between digitisation, understood as the technical process of transforming data from analogue to digital, and digitalisation, which encompasses various social dimensions.

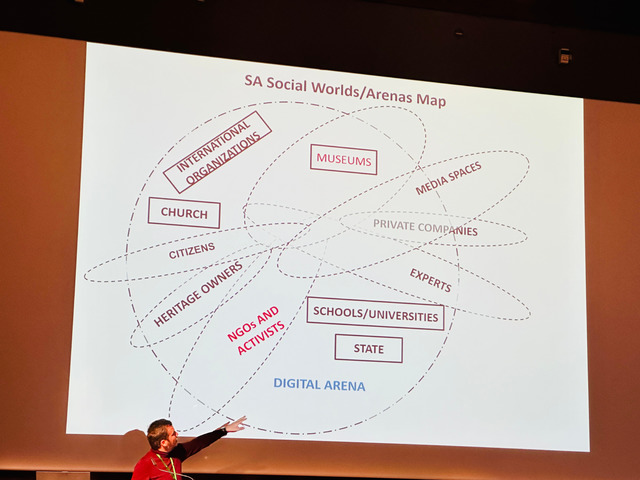

The project, conducted between October 2023 and 2025 in Austria (Graz) and Serbia (Novi Sad), examines how the process of digitalisation of cultural heritage (DCH) manifests in two types of settings: institutional (museums) and activist (citizen-led initiatives). The primary objective of the project is to investigate the plurality of discursive practices involved in DCH and their capacity to make heritage more accessible, mobilise citizens, and critically engage them with heritage. Furthermore, the project aims to demonstrate that digitalisation is not merely a technological practice, but a complex process that reflects social dimensions beyond culture.

In the age of digitalisation, technology does not play the role of a neutral ally in the evaluation and dissemination of culture. DCH in museums has become one of the crucial dimensions of communication between cultural institutions and society. Museums are often regarded as spaces where cultural values, cultural policies, property, and knowledge are institutionalised. As such, museums have been interacting with nation-, state-, and identity-building processes since their inception. But their social and cultural roles have become increasingly nuanced in the digital era. The inexorable growth of digital technology over the last few decades has transformed the way museum collections are preserved, studied, shared, and accessed.

Digitalisation often begins in archives, museums, or libraries. However, individuals, groups, or other citizen-led or civil society initiatives also play a significant role in initiating the process, particularly when it comes to neglected segments of cultural heritage. The involvement of social actors beyond museums in this practice thus creates space for evaluating forms of participation and the emergence of social inclusion or exclusion.

The participatory model of research and the understanding of the social and cultural role of museums today acknowledges the importance of diverse cultural actors who collectively contribute to understanding the complexity of heritage and the ways in which it is documented, preserved, and disseminated. At the same time, there appears to be considerable opportunity for museums to recognise the significance of (neglected) cultural objects and practices, potentially reshaping traditional frameworks and approaches to culture and heritage.

This is not about measuring importance or merit. It is about recognising the significance of various actors, especially those who are silent or have been silenced. In the era of digital communication and networks, communities or groups sometimes respond or act much faster than institutions, initiating change. Consequently, the symbiosis of different actors in the cultural field appears to offer a balance between stability and sustainability, endurance and transformation. Digitalisation thus synthesises both the need for institutional standardisation, sustainability and quality control in the process, as well as the lived experiences of people, encompassing their diverse cultural interests and needs.

Stuart Hall highlighted the relevance of a discursive approach to heritage, viewing it as a social construction and interaction—a result of the selective presentation and emphasis of certain historical and cultural elements from the past. Since cultural memory is always selective, a discursive approach seeks to recognise the valuable potential of digital technologies. This potential lies in unlocking the multiple narratives of museum objects and contributing to the reconstruction of their histories and contexts.

Digital technologies not only enhance immersive experiences and encourage audiences to engage through multiple channels, but they also enable museums to diversify heritage narratives and advocate for inclusivity. Thus, DCH represents a social assemblage—a tool for critique and social transformation. It demonstrates how it is possible to preserve the past, understand it, and simultaneously transform its meanings. It becomes a key resource for appreciating and advancing culture in the future.

Acknowledgement

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or European Research Executive Agency (REA). Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

>>> more information about the project

>>> more information about the project

Credits und Zusatzinfos:

References

References

- Aronsson P. 2015. National museums as cultural constitutions. In P. Aronsson, & G. Elgenius (eds) National Museums and Nationbuilging in Europe 1750-2010: Mobilization and legitimacy, continuity and change, 167–199. London-New York: Routledge.

- Bennett, T. 1995. The Birth of the Museum: history, theory, politics. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bernard E., Catoni M.L. 2022. Museums as Living Organisms: Temporality and Change in Museum Institutions. Il capitale culturale: Studies on the Value of Cultural Heritage n.26: p.109–139.

- Capurro, C. 2023. Digitality as a cultural policy instrument: Europeana and the Europeanisation of digital heritage. In R. Harrison, N. Dias & K. Kristiansen (eds) Critical Heritage Studies and the Futures of Europe, 223–242. London: UCL Press.

- Colomer, L. 2023. Participation and cultural heritage management in Norway. Who, when, and how people participate. International Journal of Cultural Policy 30(6): p.728–745. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2023.2265940

- Hall, S. 2004. Whose Heritage? Un-settling ’The Heritage’, Re-Imagining the Post-Nation. In J. Littler & R. Naidoo (eds) The Politics of Heritage: The Legacies of Race, 13–26. London: Routledge.

- Moutinho, M., & Primo, J. 2017. Sociomuseology’s theoretical frames of reference, Keynote at the International Conference The Subjective Museum? The impact of participative strategies on the museum, Historisches Museum Frankfurt & Department of Museology of the Universidade Lusófona, Historisches Museum Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main, 26-28th July 2017. Available at: www.mariomoutinho.pt/images/PDFs/ArtigosMuseologia/2018references_Mirrors_e-book2_24-35.pdf

- Portalés, C., Rodrigues, J.M.F., Rodrigues Gonçalves, A., Alba, E., Sebastián, J. 2018. Digital Cultural Heritage. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2(58). https://doi.org/10.3390/mti2030058

- Silverman, R.A. 2015. Museum as Process: Translating Local and Global Knowledges. London and New York: Routledge.